In the fast-paced world of automotive technology, last week marked the 17th meeting of the Working Party on Automated and Connected Vehicles (GRVA), a crucial arm of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). This gathering delved into the regulatory intricacies of cutting-edge driving assistance systems as laid out in UN Regulation No. 79, No. 157 and the eagerly awaited DCAS Regulation. Another topic was also how to incorporate AI in the development of self-driving cars and its regulation. They discussed a lot more but this falls outside the scope of this article. In this article you will learn about the governing bodies and actors responsible in the UN for vehicle regulations, the history of regulations, the outcome of the latest GRVA meeting and my opinion/vision for the near future.

What is WP.29 and GRVA?

The World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations (WP.29) is like the cool, global clubhouse for countries to agree on standards for vehicles. Picture this: different countries have different rules for cars, buses, and trucks. It's like everyone speaking their own automotive language. WP.29 brings them together and says, "Let's agree on some common rules, so when you make a car here, it can be driven there without any hiccups." They're like the peacemakers of the road, ensuring that vehicles worldwide play by the same set of rules to make roads safer and the car industry more efficient.

Understanding the Players: UNECE, GRVA, and WP.29

ITC: The Inland Transport Committee (ITC) is the UN platform for domestic transport to efficiently address global and regional needs in the field of domestic transport. Over the past 75 years, the ITC, along with its subsidiaries, has provided an intergovernmental forum where UNECE and United Nations member states come together to forge instruments for economic cooperation and negotiate and adopt international legal instruments for domestic transport.

These legal instruments are considered indispensable for the development of efficient, harmonized, and integrated, safe, and sustainable domestic transport systems.

UNECE: The UNECE serves as the overarching body orchestrating international collaboration on regulatory standards, and within its fold, the GRVA is the brain trust focused on the intricate realm of automated and connected vehicles.

GRVA: The GRVA, or the Working Party on Automated and Connected Vehicles, is the high-tech task force under UNECE. Picture them as the tech-savvy guardians ensuring our vehicles seamlessly transition into the future of automation and connectivity.

WP.29: This is the global clubhouse where countries come together to harmonize vehicle regulations. WP.29 plays the role of a mediator, fostering agreement on standards so that a car built in one corner of the world can smoothly navigate the roads in another.

Understanding the terminology

ODD: Think of the Operational Design Domain (ODD) as the "comfort zone" for autonomous vehicles. It's like defining where and how these smart machines can safely operate. The ODD sets the boundaries, specifying the environmental conditions, road types, and other factors where the autonomous system is designed to function.For example, a self-driving car might have an ODD that includes clear roads, good weather, and moderate traffic conditions. If it encounters heavy rain or a complex city environment, it might be outside its ODD, and the human driver would need to take over.

ADS: Autonomous Driving System. This is the design intent for systems like FSD. Imagine a Tesla but then without a steering wheel. The car will drive itself in every possible situation. An ADS is classified according to the J3016 as Levels 4 and 5.

ADAS: Advanced Driver Assistance System. All driver assist systems such as cruise control, traffic aware cruise control, ABS, AEB, lane assist fall under this terminology. It’s an umbrella term for L1 and L2 driver assistance systems. The UN Regulation No. 79 dictates what these technologies can and cannot do.

AV: Automated and/or autonomous vehicle. This is perhaps the most straightforward of all terms. A vehicle that drives completely autonomously. There is a subtle difference though. Automated vehicles are not synonymous with autonomous vehicles. An automated vehicle is programmed to navigate a certain area but cannot autonomously navigate unknown territory whereas an autonomous vehicle is capable of navigating all places, everywhere in the world.

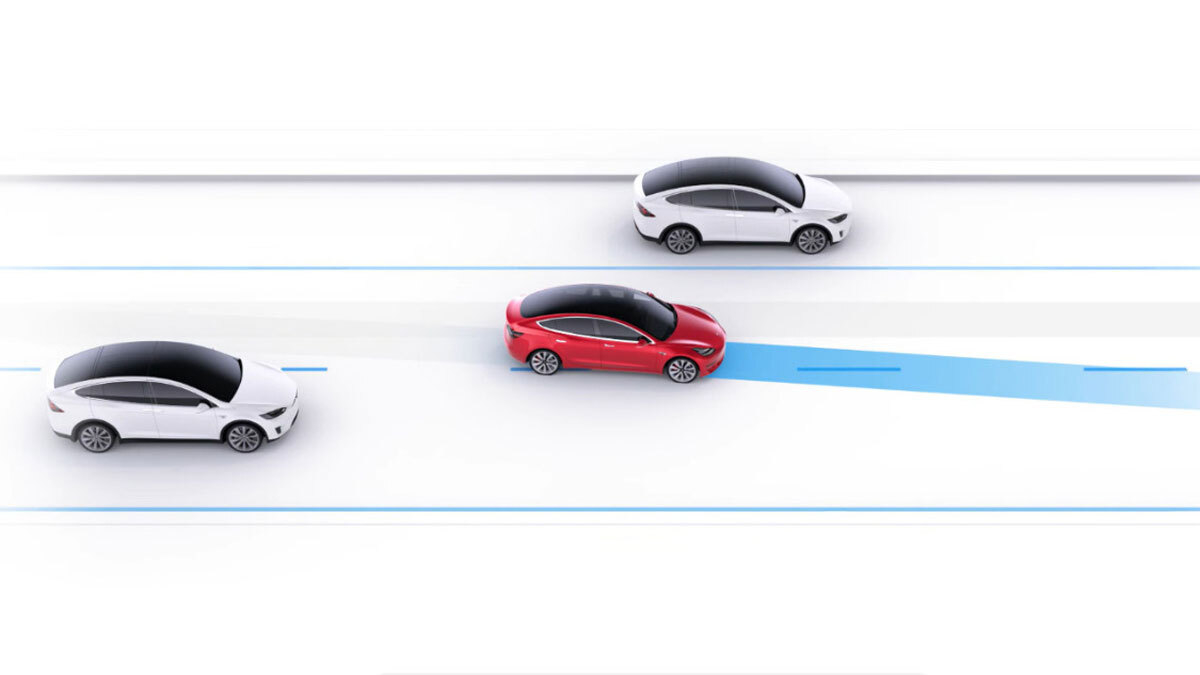

ALKS: Automated Lane Keeping Systems. Most OEMs nowadays develop or offer lane keeping systems. Some are more advanced than others. Where some systems kind of drift in the lane or help with steering to stay in the lane but others, like Tesla’s Autopilot, decisively take of the steering function and stay centered in the lane and don’t allow for driver input to correct the path.

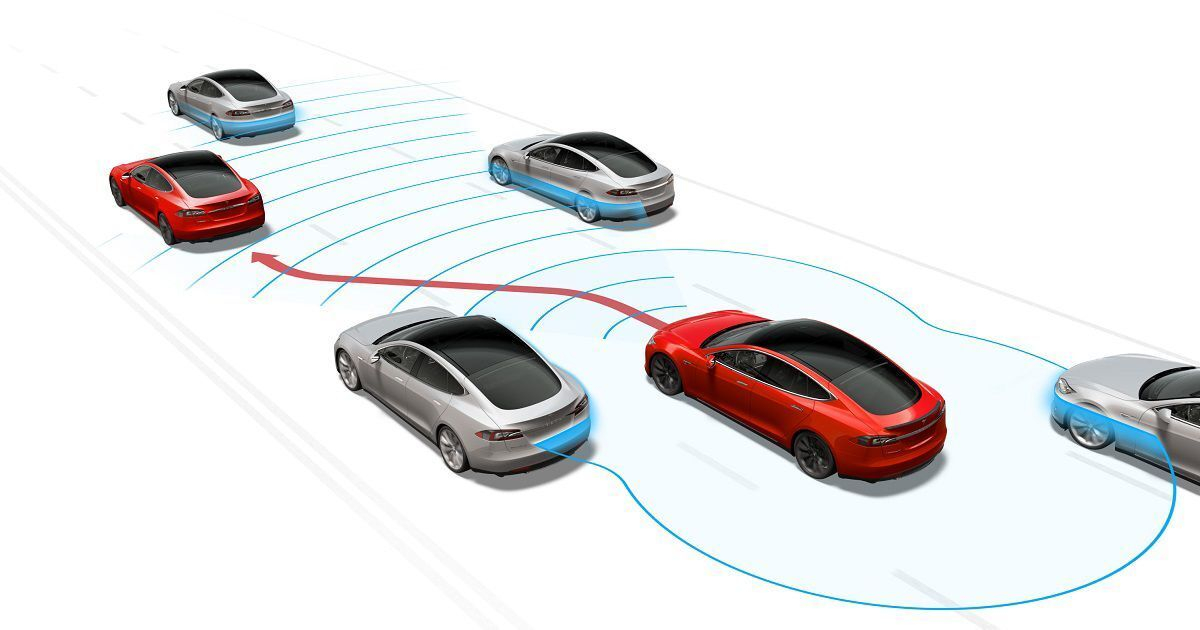

ACSF: Automatically Commanded Steering Function. This involves extra functionalities such as Lane Change Manoeuvres. This can either be driver initiated or system initiated.

The Geneva Convention on Road Traffic Safety

In the bustling world of international road travel, the Geneva Convention on Road Traffic Safety stands as a milestone agreement that has shaped the way we navigate the asphalt pathways across borders throughout the world. Let's take a journey through the annals of time to understand its evolution and the challenges it faces in the era of autonomous vehicles.

Born in 1949, the Geneva Convention on Road Traffic emerged from a collaboration among nations to establish a common framework for road safety. Later, this evolved into the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic.

The Vienna Convention on Road Traffic, commonly known as the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic, is an international treaty designed to facilitate international road traffic and enhance traffic safety by establishing standard traffic rules among the contracting parties. Imagine this: Europe after World War II, where countries were eager to rebuild and reconnect. The need for standardized rules for road traffic became evident, leading to the birth of this convention.

From driver to self-driving system

At the core of most articles, the convention centers around the concept of 'the driver.' It establishes the roles, responsibilities, and behaviors expected from individuals behind the wheel, creating a universal language for road conduct. Sadly this notion of ‘the driver’ has never been clearly defined. Mostly because it has never been necessary and it was self-explanatory that a car is driven by a human driver.

Over the years, the Geneva Convention has evolved, adapting to technological advancements and changing traffic dynamics. It has been the guiding light for road signs, traffic signals, and the fundamental principles that keep our roads safe and efficient.

However, with the advent of autonomous vehicles, a new challenge has emerged—one deeply rooted in the convention's emphasis on 'the driver.'

Autonomous vehicles, equipped with cutting-edge technology, challenge the convention's traditional understanding of 'the driver.' The very essence of autonomy lies in the diminishing role of a human driver, with systems taking over critical functions.

The Geneva Convention, designed with a human-centric perspective, faces a shortfall when it comes to legislating for autonomous vehicles. The idea of 'the driver' being a human entity navigating the roads clashes with the concept of self-driving cars, where the driver may be more of a supervisor than an active participant.

As we stand at the intersection of tradition and innovation, the challenge is to update road traffic conventions to accommodate the revolution of autonomous driving. New regulations need to address the nuances of autonomous systems, defining their roles, responsibilities, and interactions with other road users. While the Geneva Convention on Road Traffic Safety has served as a cornerstone for road travel, its evolution must now extend to include the autonomous era.

Redefining the ‘driver’

Since 2015 we have seen the rise of different Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) where this undefined concept of the driver became more apparent. From the year 2021 onward, there has been a proposal to redefine automated driving systems in Article 1 of the Convention on Road Traffic. According to this proposed definition, an automated driving system is described as a vehicle system utilizing both hardware and software to consistently exercise dynamic control over a vehicle.

Dynamic control, in turn, is clarified as the execution of all real-time operational and tactical functions necessary for the vehicle's movement. This encompasses managing the vehicle's lateral and longitudinal motion, monitoring the road environment, responding to traffic events, and planning and signaling for various maneuvers. This proposed redefinition reflects a paradigm shift in acknowledging the evolving landscape of vehicle operation and the integration of advanced technologies into the driving experience.

The Buzz around UN Regulation No. 157 and No. 79

The spotlight of the recent GRVA meeting was on DCAS and UN Regulation No. 157 & 79, crucial pieces of legislation governing Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS). Picture your car with a helpful co-pilot—this regulation is the rulebook for Level 2 automation, as defined by the SAE's J3016 taxonomy.

The J3016 taxonomy from the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) is essentially a way to classify levels of driving automation in vehicles. It breaks down automation into different levels, from Level 0 (no automation) to Level 5 (full automation). Each level represents a different degree of automation and driver involvement. It's like a roadmap for understanding how much control a vehicle can take over from the driver. For example, at Level 2, your car might handle some tasks like steering and acceleration, but you still need to keep an eye on things. At Level 5, you could theoretically take a nap, and the car does everything.

UN Regulation No. 157 focuses on Automated Lane Keeping Systems where all ADAS are classified as Level 2 systems, where your car assists with tasks like steering and acceleration. There are however some ODD’s where ADAS is classified as Level 3 where the driver is not responsible. This for instance is Mercedes-Benz’s DrivePilot which fully complies with UN Regulation No. 157. The ODD in which it’s L3 is quite limited so in essence it is nothing more than a traffic jam assist. UN Regulation No. 79 focuses on the Automatically Commanded Steering Function. This is for ADAS which can also perform lane changes and highway exits for instance. Some argue it's a bit too restrictive for systems capable of much more than just navigating through traffic jams.

As ADAS got more advanced and equipped with more capabilities, think of Enhanced Autopilot and FSD, the UN Regulation No. 159 and 79 became too restrictive and multiple laws and guidelines started to conflict with one another. This resulted in the downgrading of software that worked perfectly fine. Think of Enhanced Autopilot where the car and software could automatically merge on and off highways, could take corners a lot better than it does lately. This called for a new set of rules and regulations.

The Rise of DCAS Legislation: Paving the Way for FSD Beta

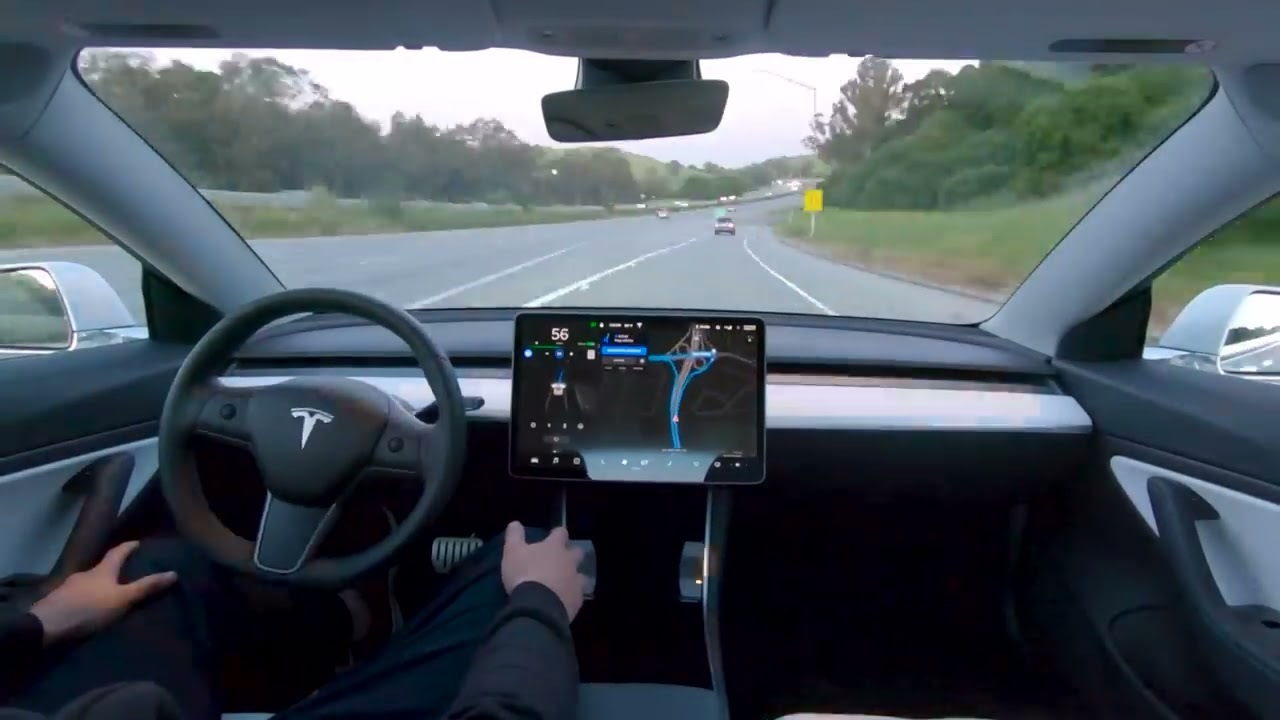

Enter the Driver Controlled Assistance Systems (DCAS) legislation—a new chapter in driving regulations. This legislation acknowledges Level 2 systems where the driver is still responsible but the vehicle and system boast capabilities beyond Level 2. Which is publicly known or referred to as Level 2+. This opens the door for systems like Tesla’s Full Self-Driving (FSD) Beta, a significant leap toward autonomous driving.

Why is the EU lagging behind? This question I get asked frequently. First of all, legislation for this does not take place on the EU level but on a higher level between nations worldwide. There is an important distinction to be made. In the US, freedom rules. Everything is legal by default until a precedent takes place and serves as a trigger for new legislation. This is why litigation is much more a thing that it is on our side of the ocean.

Over here the starting point is completely different. Here everything is illegal by default and legislation needs to be in place before the product comes to market. Therefore an unfinished product like an FSD Beta version will never be allowed to become available for consumers like it does in the United States. This attitude is generally good but it seriously damages the advent of self-learning systems because the system needs mistakes and a lot of them just as it needs good examples and a lot of them in order to learn and improve. In the US this resulted in a giant leap of FSD capabilities and a lot of data to keep on improving but also serves as justification for public release.

The Promise of DCAS:

While the final draft of the DCAS legislation wasn't ready for submission during the recent GRVA meeting, there's hope that it could still hit the desks before the end of October. If accepted, this legislation might become active from 2024 onwards, paving the regulatory way for advanced autonomous capabilities.

The main benefit of DCAS is that it allows vehicles which are or can be equipped with software with capabilities belonging to Level 4 and Level 5 autonomy but the driver is still responsible. In that scenario the technology can be set free and drive around and make mistakes, just like any new student driver would, and learn from its mistakes. With every human intervention the data from the car gets sent back and fed into a data training center and then the system will and can improve. The key to improving and developing this technology is data. The more the better and guess which company has the data high ground in this.

Road Ahead: Potential Voting and Future Implications

The anticipation is high, as stakeholders hope for a swift submission and subsequent voting on the DCAS legislation. If all goes well, we could see this regulatory framework shaping the landscape of automated driving from 2024. However, there's also a chance of postponement, with the World Forum potentially making the decisive vote in the coming year. This means that the proposal will be voted on, accepted, ratified and will go into effect from January 2025.

My conclusion

In a nutshell, these discussions and regulations are not just bureaucratic jargon. However slow it might seem, they are the compass guiding the integration of cutting-edge technology into our everyday commute, ensuring safety, efficiency, and a standardized global driving experience. For some and arguably most people legislation goes painstakingly slow. But bear in mind that the UNECE legislation covers around 80 nations across the globe so it will have a severe impact if this is not done correctly.

I do however acknowledge that making legislation for each different driver assistance system makes no sense and seriously impedes the development of self-driving technology. Besides that it is practically impossible in my opinion to make definitive legislation for technology that moves at an incredible pace. It’s a lot more beneficial to make general guidelines and let technology further develop and steer where necessary.

The coming into effect of DCAS will serve as a major catalyst for self-driving cars and technology in UNECE member states and puts an end, for now, to liability issues and promotes human agency and responsibility to achieve a common goal, as set forward in the 1958 agreement, making the roads safer for everybody and in doing so rising productivity output of all human beings normally stuck in traffic. I will continue to keep an eye on these developments—they are steering us into the future of transportation.